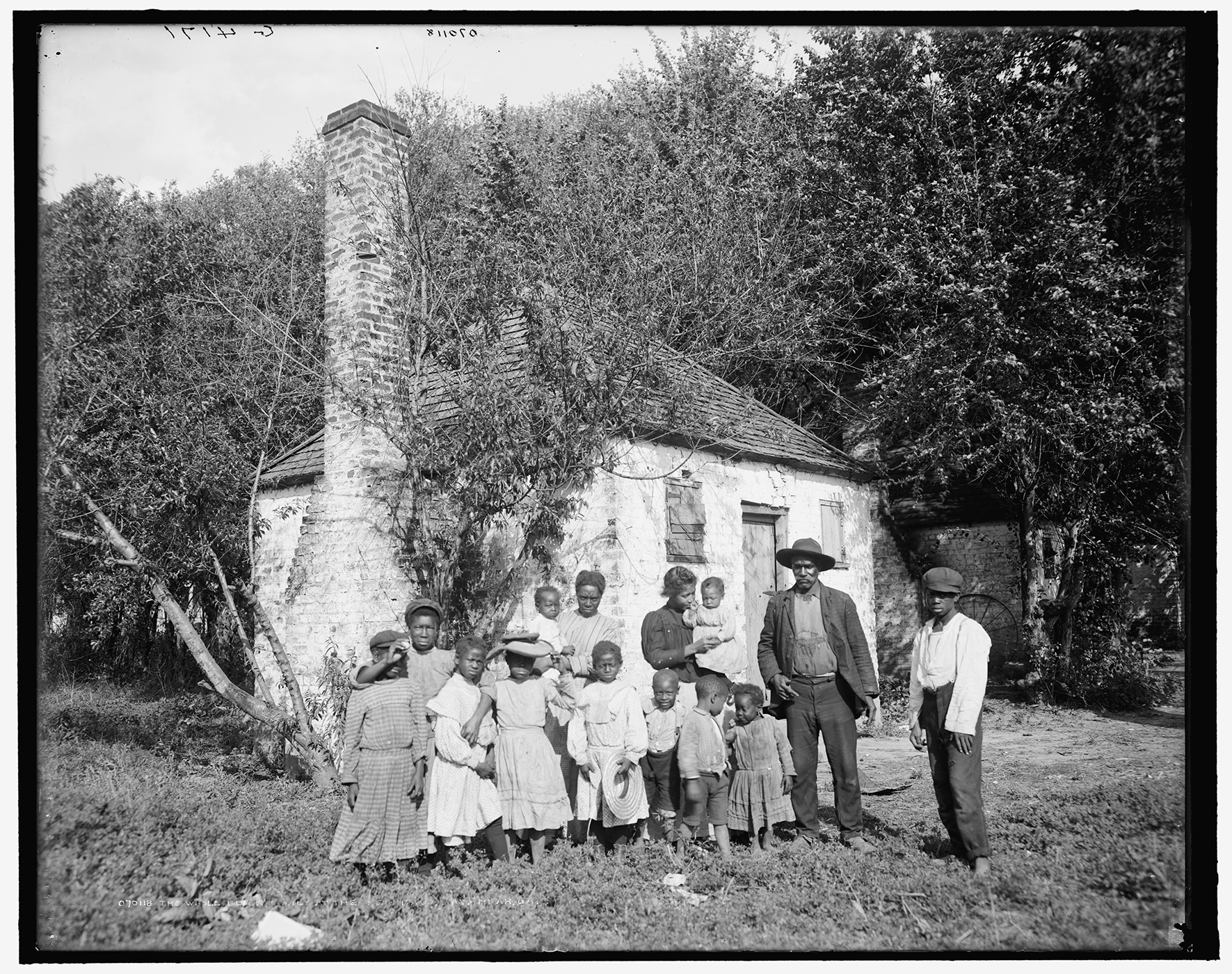

Interpreting the architecture of slavery must be an interdisciplinary process and done on a holistic level. The interpretation of slave house architecture, in combination with details from the historical record and stories from actual inhabitants, offers an opportunity to more fully understand and authentically interpret the lifeways and settings of an enslaved people in America. It is critical to interpret a slave house from the inside out, revealing the sacred space in which the enslaved could exercise some degree of control over their lives.

Methodology

Construction and physical details of slave houses, incidental details and personal markings (such as carvings and drawings), ex-slave narratives, plantation management records, census data, tax documents, Bills of Sale and probate records are all used to interpret a space. Details from these sources provide insight about the number of people who lived in each house and for what length of time. Plantation management records are used to interpret quality of life situations for enslaved people. “Slave Rolls” list the names of individual people and help humanize the people who lived and worked in these buildings. Birth records provide ages of individuals and sometimes parentage, as well as shed light on breeding strategies. Records of work schedules, food rations and clothes, cloth and shoe distributions are used to interpret what activities took place outside the slave houses, what was cooked in the hearths and personal chores that had to be done within the house in order to survive.

It is important to remember that slavery was different for every single person who experienced it, free, freed or enslaved. There are broad patterns and similarities between daily life for people enslaved from one site to the next; but, in order to truly begin to understand the human dimensions associated with slave house one must carefully consider the descriptions given by someone who actually lived and worked in the buildings. One of my project methodologies, known as “In Their Own Words,” can definitively identify the ex-slave narratives that describe a specific documented slave house. In this context, the house where the formerly enslaved person lived during slavery is the same house featured in the image.

For example, the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) and the Federal Writers’ Project were two large-scale government survey projects from the 1930s that, in part, documented slavery in America. HABS-documented the architecture and created a graphic representation of a site, while the Writers’ Project recorded American life histories from ex-slaves.

Historically stakeholders utilized these resources in isolation of one another. Through my research coordination between the two programs was proven effective. Of the 485 HABS sites with a documented slave house and the 1,010 ex-slave narratives that describe their house during slavery, only 5 documented slave houses from the HABS collection can be directly linked to a slave narrative recorded by the Writers’ Project.

The Slave Narratives are a critical and accurate interpretive tool because they describe the spaces from actual inhabitants who lived and worked within them. They provide details about the houses that fuse a voice about the human condition with the physical structure.

The Slave Narratives bring to life the spatial density, degree of accommodations, nature of the facilities, and attitudes of those who inhabited the slave house. The relationship between the historical record and the stories of the inhabitants are crucial to our understanding and interpretation of the lifeways and settings of an enslaved people in the antebellum South. In doing so, the plantation landscape is revealed not through the eyes of the master but through the perspective of those who were in his charge.